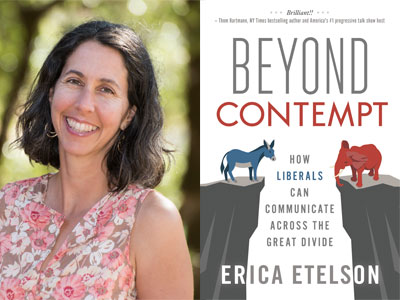

Good People for the Resistance is a monthly interview with people who give me hope. This week, meet Berkeley, CA-based writer Erica Etelson. In her new book, Beyond Contempt: How Liberals Can Communicate Across the Great Divide, Etelson takes on the gargantuan task of urging liberals to stop demonizing Trump, and start speaking to his supporters with curiosity and respect.

As a person experiencing severe “contempt fatigue,” I was excited to learn of Erica’s book. Reading it, my feelings vacillated between contempt for Trump and his supporters, guilt that I feel so much contempt, and gratitude that Erica wrote this book. Learn why Trump-related contempt is like Doritos — it makes us feel good for a moment, but that feeling just doesn’t last.

Q: You start Beyond Contempt by confessing that as of November 9, 2016 you felt unbridled contempt for Trump and his supporters (a.k.a., Those People), who you described as “crazy, racist, misogynistic, gun-toting knuckleheads who voted for a self-aggrandizing, mono-syllabic, bilious, billionaire charlatan who would obviously stab them in the back as they sat in front of their TVs, being lobotomized by Sean Hannity while swilling non-craft beer.” Now you are advocating that we sit down and share a non-craft beer with Those People. What caused your seismic shift?

My “contempt high” starting wearing off when it dawned on me that the way I and my fellow lefties were talking about Trump and his base contradicted all of the principles I had learned in my years of study of Powerful Non-Defensive Communication (PNDC), which taught me how to communicate without being defensive or feeling superior. And I started thinking, wow, every time I ridicule and lambast “These People,” I’m driving them deeper into Trump’s corner, just like Hillary did when she called them deplorable.

So I wrote an article for Alternet about how to talk to Trump voters and it went viral, which never happens with my articles, and I thought—aha, I’ve hit a nerve. And then, I got an email from a Republican who had read my article, and he wrote: “I give you a begrudging hat tip. You hit the nail on the head. I don’t think I want to share your article on Facebook because I don’t want liberals to learn the lesson you’re trying to teach them—I’d rather they keep shooting themselves in the foot.” And that email got me thinking I should turn the article into a book.

Q: You write that contempt is “Junk food for the soul.” What’s this mean?

It’s pleasurable to feel contemptuous—there’s evidence that it activates regions of the brain that produce adrenaline and dopamine, which makes it addictive, like junk food. It’s fun in the moment but it left me feeling icky, and I don’t miss feeling that way.

Q: Does your Trump-related contempt ever return? Do you have a trigger?

When I read the news now, my reaction is more in the realm of pure rage or sadness, rather than contempt, which is a blend of anger, disgust and superiority. Sometimes, a comedian who’s ridiculing Trump can awaken my contempt but I’ve cut way back on that, and my anti-contempt reflex kicks in pretty quickly now.

Q: You give lots of advice on how to talk to Trump supporters. The first step is to ask “curiosity-based” questions. Can you give me an example? Why’s this a good starting point?

Curiosity takes us out of judgment and out of the need to convince the other person that we’re right and they’re wrong. The best kind of curiosity question comes from a place of simply wanting to understand why the other person believes or values the things they do. For example, if someone is saying they don’t trust climate scientists, I might ask, “Do you see them as intentionally lying or innocently mistaken?” or “Are there any climate scientists you trust?” Then, if they say they think they’re lying, I could ask, “What makes you believe they would lie about it?” or “What do you think their motives are for lying?”

Q: During these conversations you suggest we don’t try to change anyone’s mind, rather simply invite the person to consider what we’re saying. What’s the goal – to find a way to get the person to listen?

I invite the other person to listen. The paradox at the heart of all this is that, the more you try to convince the other person, the less likely you are to do so. So, the way I approach it now is just, okay, I’m here to understand where you’re coming from and to tell you where I’m coming from and then we’re going to walk away, and I’ll either have planted a seed or I won’t have, and life goes on (hopefully). This is absolutely the hardest part for me because, as an activist and a former lawyer, I’m hardwired to want to persuade the other person and it’s challenging to set aside that agenda.

Q: You state (correctly!) that liberals often throw up our hands in despair over “right-wing fact-resistance and Trump’s sinister undermining of the very notion of truth.” It’s a fact that Trump lies. It’s a fact that many Trump supporters believe many of his lies. How are we supposed to have a conversation with someone who does not believe in facts that are true?

All we can really do is state what we believe to be true and to say something, in a non-condescending way, about why we question what they believe to be true. I’m working on an article right now about how to deal with this whole vexing issue of fake news and “alt-facts.” But spoiler alert–there’s no silver bullet and, until the Fairness Doctrine is restored and Facebook regulated and the dark money in politics brought to heel, I’m afraid we’re going to be stuck with this problem in a big way.

Q: Reading your book, my feelings vacillated between contempt for Trump and his supporters, guilt that I still feel so much contempt, and gratitude that there are people like you willing to keeping trying. Is this normal?

I certainly understand the mix of reactions you’re describing, and I cycle through all of them myself. I have enormous gratitude for people like Sharon Ellison, who created PNDC, and to people like Martin Luther King who was so steadfast in his belief in honoring the humanity of all people, even the oppressors.

Q: If you had a chance to ask Trump one question, what would it be?

It’s incredibly tricky with Trump because most questions simply provide a platform for him to self-aggrandize or to dismiss the question as “fake news.” So I’m inclined to ask a question about his beliefs: “Do you believe that a sitting president should abide by the same laws as any other citizen, or do you think there are laws that they don’t have to or shouldn’t have to comply with, and if so, what are those laws?” Or, if I had the chance to ask him a question right after he said something insulting, I’d ask, “How does it make you feel when you say something cutting about someone you don’t like?” For someone with low self-awareness, that’s a hard question to answer without coming across as sadistic.

Q: You live in Berkeley, California, one of the most liberal cities in the country. (4% of registered voters are Republican). Do you ever get a chance to talk to Trump supporters at home? If not, where do you go to practice?

I get outside my Berkeley bubble by canvassing in a swing district in the Central Valley that we flipped in the mid-terms. And last October, I went on a lark to Kentucky to canvass with Working America in the gubernatorial election that the Democrat won by 5,000 votes. I definitely heard some things there that I don’t typically hear in Berkeley.

I also participate in two groups–Better Angels and Living Room Conversations-– that host cross-partisan dialogues.

Q: Who’s your Dream Team for president and v.p. in 2020?

I’d rather not say. My book is for everyone left of center and, if I endorse someone, I’m concerned that people who favor another candidate might think this book isn’t for them.

I’m so happy to learn there are people working to heal our divide! In the case of living room conversations, since 2010. Fantastic. Thank you for your efforts and for sharing this valuable information! We need it desperately!

I cannot recommend PNDC and Sharon Ellison highly enough. Common sense, yet transformational. Do check it out.